The Death of ‘Development’

Trump's Tariffs mark the end of the dominant model of Global Development following its long decline. What now?

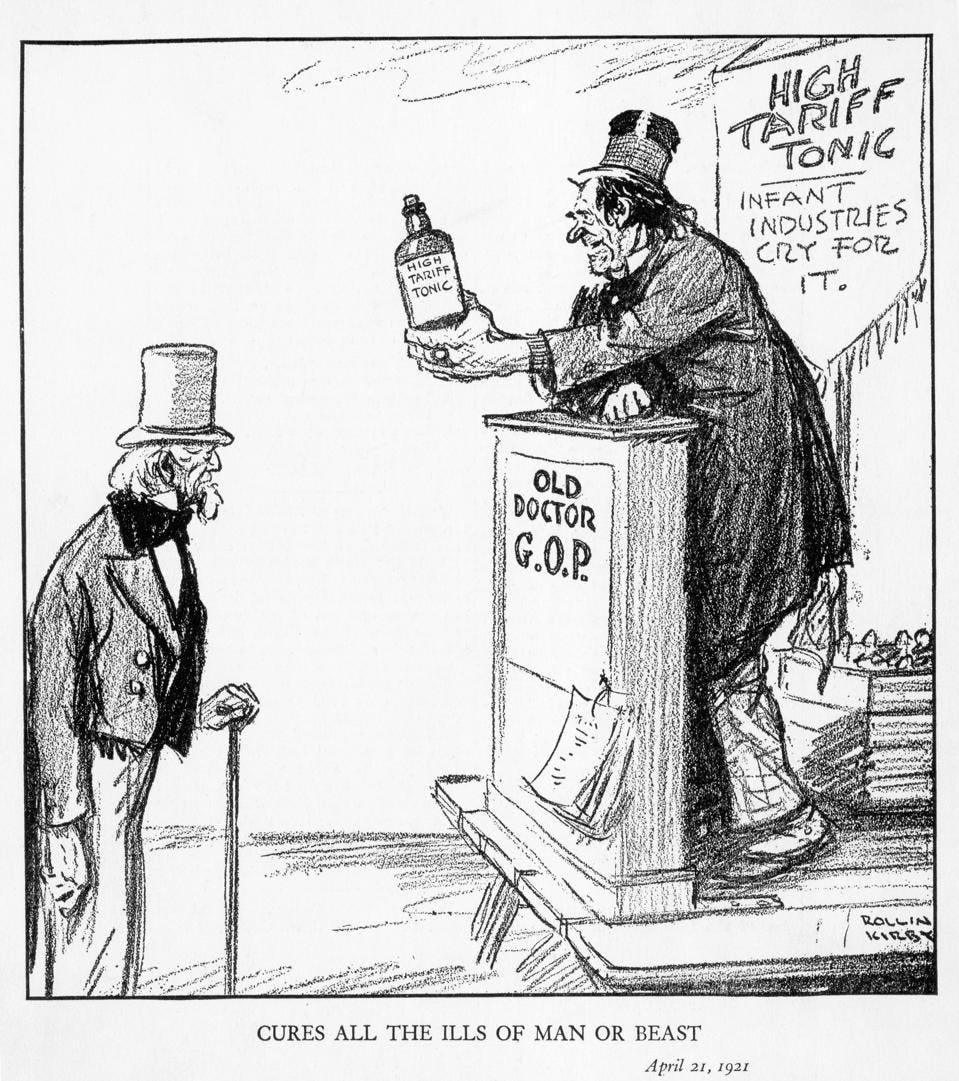

(Illustration by Rollin Kirby.)

The sweeping, near-universal tariffs announced by the Trump administration yesterday, with particularly punitive rates targeting nations like China, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, represent more than just another trade conflict. They constitute a fundamental rupture, marking the end of the post-war development model that, for all its flaws and inherent difficulties, shaped the global economy for three-quarters of a century. This is not merely about economic disruption; it is about the end of the framework widely understood as the way poorer nations could aspire to converge with the rich world.

This article is deeply informed by David Oks’ and Henry Williams’ "The Long, Slow Death of Global Development" published in American Affairs in 2022. It is, in my view, one of the most essential pieces in recent years. They compellingly argue that the optimistic narrative surrounding global development in the early 21st century was already deeply flawed, masking structural weaknesses and premature deindustrialization across much of the Global South.

Crucially, they demonstrate how the extraordinary progress in poverty reduction was overwhelmingly concentrated in China and East Asia; remove China from the statistics, and the picture of global development over the last half-century looks depressing. The recent tariff announcements can be seen as potentially delivering a final, decisive blow to the already faltering development model Oks and Williams so effectively diagnosed.

The Post-War Model: Promise and Problems

The history of development, particularly since 1945, is largely the story of integration into a US-led global economic order and the establishment of rules predicated on expanding trade. The dominant model, exemplified first by Japan, then the East Asian tigers, and most dramatically by China, was one of export-oriented industrialisation. Poorer countries could leverage low labour costs to manufacture goods for consumption in richer markets, principally the United States, which acted as the global consumer of last resort. This generated foreign exchange, facilitated technology transfer, and spurred domestic investment, driving structural transformation and lifting living standards.However, as Oks and Williams detailed, development within this globalised system proved extraordinarily difficult over the last half-century.

There is no simple formula for development. Global economic integration brought challenges: vulnerability to volatile global capital flows, intense competition often keeping developing countries locked into low-value activities, and the challenge of building domestic capabilities.

Yet, despite these inherent difficulties, the relatively low tariff barriers maintained by developed countries, particularly the US, did offer a crucial, tangible pathway. This pathway allowed developing nations to utilize their comparative advantage in lower labour costs to build manufacturing export sectors. Selling goods into the vast, wealthy markets of the North could provide foreign exchange, foster industrialisation, and create desperately needed jobs. However, as starkly illustrated in the American Affairs piece, this model has been fraying for some time. The uncomfortable truth is that much of the dramatic reduction in global poverty over the past four decades is overwhelmingly attributable to China.

The China Exception and a Fragile System

Its success in lifting perhaps a billion people from destitution is an achievement of historic proportions. However, strip China out of the data, and global development was far flatter, almost stagnant. Furthermore, China's own miracle was deeply intertwined with, and reliant upon, access to the vast US market. The engine of global development and poverty reduction, it turns out, was heavily dependent on the continued openness of the American economy.

Recent examples underscore this relationship. Vietnam, for instance, has achieved remarkable progress through export-led growth, becoming a significant manufacturing hub, particularly as companies sought alternatives to China. A crucial pillar of this success has been its burgeoning trade relationship with the United States. The imposition of broad tariffs strikes at the heart of such strategies. Indeed, the implementation of these measures, especially the high rates against key Asian manufacturing exporters, deals a direct blow to this model, effectively pulling up the ladder for countries attempting to follow this path. The immediate consequences will be severe. Developing countries reliant on exports to the US face crippling economic shocks.

Furthermore, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), a key pursuit for developing countries aiming to establish export platforms, is fundamentally undermined. If the cost advantage of producing in a lower-wage country is nullified by tariffs, the incentive for much manufacturing FDI evaporates, threatening vital development-supporting capital flows.

The damage will also be sharply reciprocal. The US itself will face disrupted supply chains, higher import costs feeding inflation, and reduced competitiveness. Consider the ludicrousness of applying such tariffs to imports from Vietnam, Laos or Cambodia. Much of their export success is in highly labour-intensive manufacturing like clothing. The notion that these jobs will "come back" to the US is fanciful; American workers are unlikely to desire such employment at wages remotely competitive with Vietnam's, and American consumers are equally unlikely to accept the steep price increases necessary to cover US labour costs for basic apparel. The idea that these tariffs will address a trade imbalance is even more ludicrous; America does not produce many items that developing countries can afford in significant volume. This is not going to change with tariffs or any subsequent negotiations.

The political consequences could be even more insidious. Since the 2008 financial crisis, governments struggled to address economic stagnation and inequality, creating fertile ground for right-wing populism. Widespread economic devastation from a trade war will likely pour fuel on this fire, potentially providing cover for oligarchic interests who thrive amid nationalist rhetoric.

Worryingly, this populist surge often provides cover for oligarchic interests. As we have witnessed starkly in the US, but also elsewhere, nationalist rhetoric can be cynically deployed by economic elites as a lever to dismantle regulations, cut taxes on the wealthy, and capture state resources for private gain, further exacerbating the very inequalities that feed the discontent. The fragmentation of the global economy serves those who thrive in environments of diminished transparency and regulatory chaos.

Of course, trade will not cease entirely, as I have previously covered. Regional blocs may strengthen. But the global development consensus, underpinned by the US commitment to relatively open markets, is shattered. This is compounded by trends like declining aid and a US retreat from even nominally promoting democratic values.

A Shattered Consensus and Charting New Paths

My previous articles struck a relatively positive tone, and pointed to opportunities as these great changes occur. Yes, economic life exists outside the orbit of US trade, and countries will adapt. But given the enormous difficulties developing nations already faced, as Oks and Williams so clearly laid out, the deliberate destruction of the pathway via manufacturing exports to development, which China succesfully pursued and Vietnam and its 100+ million citizens have been fruitfully following, guarantees devastating consequences for the livelihoods and aspirations of millions.

The lights are dimming rapidly on an entire era of global economic aspiration. The era of ‘development’, as understood since 1945, was already on its knees. This week marks its final goodbye.

I don’t want to be entirely negative. The only way solutions can be found is if problems are identified. There are innumerable good people out there working to make the world a better place through collaboration and cooperation to enjoy the mutual benefits this brings. This can be a time of reflection and rethinking, to address the problems that Oks and Williams identified with the old ways, and to be bold in how to be better.

The world is dangerous, but not only because of invasions. Investments in arms will not fight poverty, will not boost health, and will not combat or protect against global warming. If the only response to the new reality is retaliatory tariffs and increased defence spending, we will go nowhere. Ryan Research provided some interesting thoughts on strategies for adjustment to this changed world from the Irish perspective. Similar creative problem-solving is a necessity the world over.

Boldness and progress now might lie in reclaiming economic sovereignty and deploying sophisticated industrial policy to build capacity in essential sectors. Crucially, it could mean harnessing the global green transition not as another wave of resource extraction, but as a primary engine for shared industrialisation and job creation through new global arrangements. This requires moving beyond simplistic offshoring and designing internationally coordinated supply chains where value is added at multiple, appropriate stages across diverse economies.

Imagine frameworks where resource-rich developing nations move beyond raw material export to refining and component manufacturing for batteries or turbines; where middle-income countries become hubs for assembly and specialized parts; and where developed nations focus on cutting-edge R&D and complex systems integration, supported by fair technology-sharing agreements and co-development initiatives. Such arrangements would need underpinning by dedicated climate finance that explicitly supports this industrial diversification in the Global South, alongside robust partnerships for skills development, ensuring nations can genuinely capture the benefits of participating in these vital new industries. This approach aligns the urgent need for decarbonization with the imperative for more equitable and resilient global development, turning a shared crisis into a potential engine for widespread progress, rather than replicating the dependencies of the past.

These are immense challenges, requiring immense political will, but the closure of old paths forces the consideration of new destinations. The task now is to channel the energy of those seeking a better world towards building these more autonomous, resilient, and perhaps ultimately more sustainable foundations for genuine human development in the twenty-first century.

Good and easy to read analysis Ros.